The past week in the Roanoke Valley has been a good one for the proper acknowledgment of history.

First came a marker for a too-long unsung Botetourt County hero. Then came a memorial acknowledging a horrific injustice that haunts Roanoke’s past.

Learning from history for the sake of charting constructive forward paths requires honest appraisals of the great and the terrible.

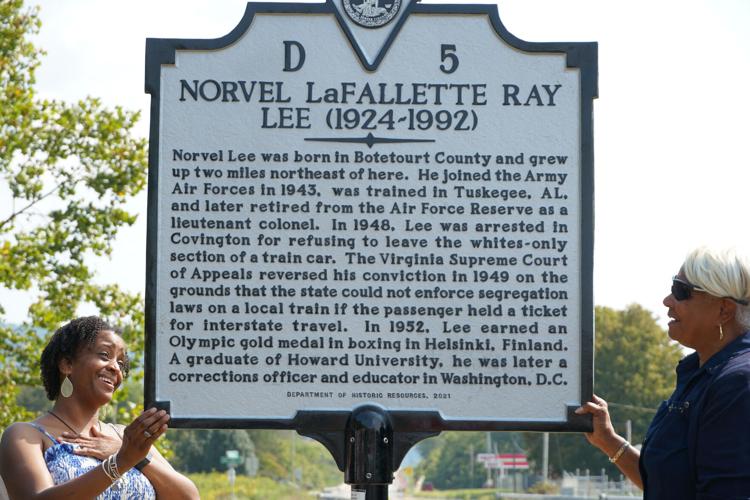

When facing adversity, Norvel LaFallette Ray Lee demonstrated greatness.

Born in 1924 near Eagle Rock, Lee was the first Black Virginian to win an Olympic gold medal, as well as the second American, and the first Black American, to win the Val Barker Trophy, bestowed every four years on the best boxer in the Olympic Games, regardless of category. He accomplished both feats boxing in the light-heavyweight division as part of the 1952 Olympic team competing in Helsinki.

People are also reading…

Jaw-dropping though they were, Lee’s Olympic triumphs were not acknowledged by the news media in his home state of Virginia. Undaunted, Lee continued to add accolade-worthy achievements both athletic and academic to his curriculum vitae.

His prowess in the boxing ring already makes him a figure of historical note, but another arguably even more important bout that he won cements his reputation as a civil rights pioneer. Arrested in Alleghany County in 1948 for refusing to give up his seat in the white section of a train car, Lee fought his conviction all the way to the Supreme Court of Virginia and won, striking a blow against the commonwealth’s odious segregation laws.

Saturday, in a ceremony attended by members of Lee’s extended family, his memory was honored with a Virginia Department of Historic Resources marker along U.S. 220 near the location of his childhood home — and that stretch of highway in northern Botetourt County now bears his name. Kudos must go to Lee’s biographer, Ken Conklin, historian and former Roanoke Mayor Nelson Harris, and Del. Terry Austin, R-Botetourt, for posthumously granting Lee a portion of the recognition that should have been his 70 years ago.

The importance of Lee’s civil rights victory comes into even starker relief when considering the more somber dedication ceremony held Wednesday in Roanoke.

Members of the Roanoke Coalition of the Equal Justice Initiative's Community Remembrance Project unveil an historical marker about the 1893 lynching of Thomas Smith during a ceremony at Franklin Road at Mountain Avenue Wednesday, Sept. 21, 2022, in Roanoke.

The Roanoke Equal Justice Initiative Community Remembrance Project Coalition, working with the Montgomery, Alabama, advocacy group that operates the National Memorial for Peace and Justice — which memorializes lynching victims and other victims of racial terror throughout the nation — unveiled a striking blue historical marker at Franklin Road and Mountain Avenue Southwest, the site where a bloodthirsty white mob lynched Thomas Smith, an innocent Black man, on Sept. 21, 1893.

Smith was seized and jailed by police after a white woman reported being assaulted and robbed. A mob demanded Smith be handed over for lynching on the spot. By the end of a dark day of astonishing bloodshed, the mob would carry out Smith’s grotesque murder, but not before an ultimately failed effort at repelling the lawless crowd by the city’s militia would leave close to 10 dead and more than 30 wounded.

In 1916, more than two decades later, the NAACP’s national journal would report that the Roanoke jailers quickly determined that Smith was the wrong man. Not only did they keep that information secret, they also hid that they had soon arrested a much more likely suspect, who was let go after promising to leave the city and never return.

The pain of this injustice and others that sprouted from the same corrupt, racist roots lingers in the Roanoke Valley. To heal, wounds must be treated, not ignored and allowed to fester. This crime cannot be undone but its public acknowledgment allows for making peace with the past.

More efforts such as these, commemorating the righteous and remembering the wronged, are underway. The EJI group will raise another marker as a reminder of the February 1892 lynching of William Lavender near the Roanoke River.

An internet project, “Roanoke Hidden Histories,” will create a virtual tour of sites significant to the history of Roanoke’s Black communities. Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman whose cancer cells have been essential to decades of biomedical research conducted after her death, was born in Roanoke, and a fundraiser to place a statue of her in a plaza by city hall is near its $160,000 goal.

So much more can and should be done, but what happened this week, and what’s coming down the pike, is necessary and promising.